“Traditional chemical photography is an extraordinarily flexible field, which, even as it disappears, has hardly been touched.”

Wayne Thiebaud on Giorgio Morandi

Appropriately, Wayne Thiebaud is exhibiting at Museo Morandi in Bologna. Read the short interview with Thiebaud in this month’s ARTnews.

“There are such good lessons to learn from looking at his work… One of them, I think, is the wonder of intimacy and the love of long looking. Of staring but at the same time moving the eye, finding out what’s really there, and there are so many things that are subtle and may look like something at one moment but not the next.”

The New Carpe Diem

http://visualsciencelab.blogspot.com/2011/10/lonely-hunter-better-hunt.html

Consider what Walker Evans told students at Yale in the sixties: “Work alone if you can… you want to concentrate; you have to. Companions you may be with, unless perfectly patient and slavish to your genius, are bored stiff with what you’re doing. This will make itself felt and ruin your concentrated, sustained purpose.”

Case in point: our last trip. Five days outta town. Quy tonestly, except for an episode involving cyclists on a bridge, the stuff I was shooting wasn’t getting the concentration it deserved–plus, there were late nights that removed the option to shoot at dawn—until the last day, when I was able to arrive at a target site before sunrise (sort of). That session was the payoff. I got to do it my way, Don Costa.

“Don’t wait for the stars to line up.”

More W. o’ W. from John Szarkowski

“It is often thought (by non-photographers) that documentary photography records something that was evident before the photograph was made, but in fact good photographs are the product of discoveries made within the process of photographing.”

“When the photographers are sharp-eyed and clear-minded their pictures can seem to describe the very flavor of the moment—the fulcrum on which the present changes to the past.”

W. o’ W.: Tod Papageorge

“I think that one source of the frustration I’ve always felt about the eventual supremacy (at least for a moment) of postmodernism, and even about staged photographs—which was something nobody seemed able to understand (outside of Szarkowski, but certainly no art historians and certainly no editors at October magazine)—is that we knew we were making fictions. We knew we were creating something, in many cases, out of nothing. Or nothing more than the conjunction of objects and people in space. The unspoken expectation was that an intelligent person would look at something like what you described and say: ‘Well, obviously that never happened. The photographer has, in effect, through perception and response and training and whatever else (such as poetic presentiment), created this, this made thing, this piece of art.’ Now, perhaps you’re not interested in it as art. Perhaps you don’t think it’s as wonderful as a James Rosenquist painting or something else. Yet it is art, something fabricated out of the unfabricated dross of passing life (while, paradoxically, still trading on the indexical heft of that dross). Unfortunately, however, it turned out that most people needed to see the literal lineaments of fabrication—the studio effect—to recognize that art-making had occurred. I’ve always believed, in fact, that it was a terrible relinquishment on the part of the so-called “intelligent audience” not to be hard enough on itself to understand that, but of course I would believe that, given my position as a photographer-in-the-world. It’s been a decades-long frustration, though, and I guess always will be one, because people tend to see photographs as simple, literal recordings of the way things were at a particular moment unless—these days through scale, color, and a certain residual sense of the embalmed that the studio and Photoshop often lend to them—they effectively brand themselves as having been deliberately manufactured.”

Read the entire interview in the current issue of Aperture.

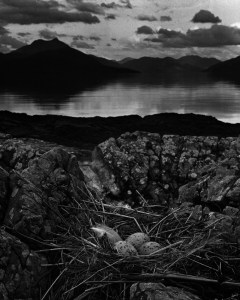

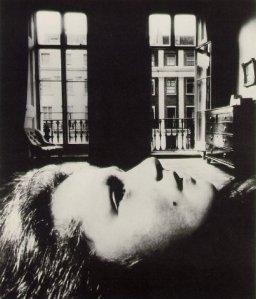

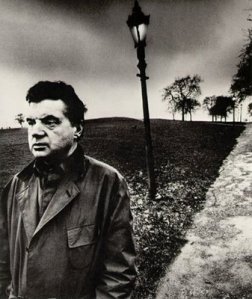

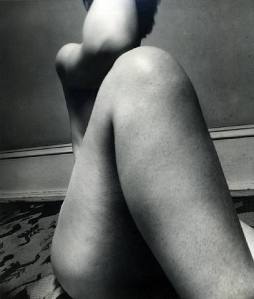

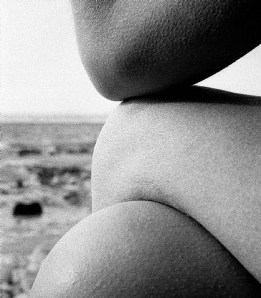

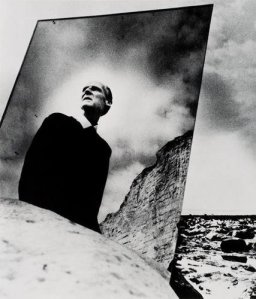

W. o’ W.: Bill Brandt

To be able to take pictures of a landscape I have to become obsessed with a particular scene. Sometimes I feel that I have been to a place long ago, and must try to recapture what I remember. When I have found a landscape which I want to photograph, I wait for the right season, the right weather, and right time of day or night, to get the picture which I know to be there.

I always take portraits in my sitter’s own surroundings. I concentrate very much on the picture as a whole and leave the sitter rather to himself. I hardly talk and barely look at him. This often seems to make people forget what is going on and any affected or self-conscious expression usually disappears. I try to avoid the fleeting expression and vivacity of a snapshot. A composed expression seems to have a more profound likeness. I think a good portrait ought to tell something of the subject’s past and suggest something of his future.

In 1926, Edward Weston wrote in his diary, “The camera sees more than the eye, so why not make use of it?” My new camera saw more and it saw differently. It created a great illusion of space, an unrealistically steep perspective, and it distorted.

When I began to photograph nudes, I let myself be guided by this camera, and instead of photographing what I saw, I photographed what the camera was seeing. I interfered very little, and the lens produced anatomical images and shapes which my eyes had never observed.

I felt that I understood what Orson Welles meant when he said “the camera is much more than a recording apparatus. It is a medium via which messages reach us from another world.”

I am not interested in rules and conventions … photography is not a sport. If I think a picture will look better brilliantly lit, I use lights, or even flash. It is the result that counts, no matter how it was achieved. I find the darkroom work most important, as I can finish the composition of a picture only under the enlarger. I do not understand why this is supposed to interfere with the truth. Photographers should follow their own judgment, and not the fads and dictates of others.

Photography is still a very new medium and everything is allowed and everything should be tried. And there are certainly no rules about the printing of a picture. Before 1951, I liked my prints dark and muddy. Now I prefer the very contrasting black-and-white effect. It looks crisper, more dramatic and very different from colour photographs.

It is essential for the photographer to know the effect of his lenses. The lens is his eye, and it makes or ruins his pictures. A feeling for composition is a great asset. I think it is very much a matter of instinct. It can perhaps be developed, but I doubt it can be learned. However, to achieve his best work, the young photographer must discover what really excites him visually. He must discover his own world.

Read the entire statement: http://www.billbrandt.com/Library/statementbybrand.html

W. o’ W.: Andrew Hill

“It’s easy to fall back upon what you’ve done, but it’s harder just to continue playing. To me it’s terrible to play without the passion of music. It’s the passion that connects, not the academic correctness. The passion brings out the magic, something that draws the audience into you. It was inspirational to discover that things aren’t static… the spirit of jazz is supposed to be built upon playing something different every time you play.”

Good news!

Oh, sure, I read “After Photography” when it was published, and I’ve been to seminars and panel discussions… now,

this just in: http://www.youtube.com/user/jmcolberg?blend=2&ob=5